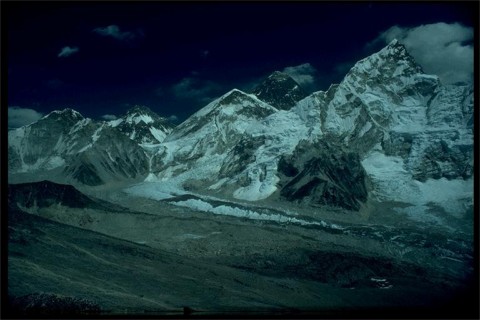

Mount Everest

|

Location:

Mount Everest is a rock and snow peak of the Himalayas. It is in Nepal and stands on the border of Tibet.

Mount Everest is a rock and snow peak of the Himalayas. It is in Nepal and stands on the border of Tibet.

History:

The expedition which first reached the summit, in 1953, was the eighth to make the attempt; there had also been three reconnaissance expeditions.

The peak was named after Sir George Everest. Its Tibetan name is Chomolungma.

The expedition which first reached the summit, in 1953, was the eighth to make the attempt; there had also been three reconnaissance expeditions.

The peak was named after Sir George Everest. Its Tibetan name is Chomolungma.

Description:

Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world. Its height is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m)

Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world. Its height is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m)

The Great Barrier Reef

|

Spanning more than 2000 km along the northeastern coast of Australia, the Great Barrier Reef is home to thousands of species of plants and animals. The Reef which runs parallel to the Queensland coast has been designated by the Australian Government as a Marine Park.

Few can imagine the biological diversity of the reef. One probably has to realize first that the 2000 km long reef runs predominantly in the North-South direction, therefore spanning a wide range of climates. Rain forests and mountains are predominant in the northern islands, while the southern islands are composed mainly of Coral Cay.

Apart from its environmental value, the area offers visitors a variety of activities including scuba diving, snorkeling, water sports, and birdwatching.

The Grand Canyon

|

The Grand Canyon of the Colorado River is the largest gorge in the world-a 290-mile-long gash across the face of the Colorado Plateau in northern Arizona. Rim to rim, it measures up to 18 miles across, with an average width of 10 miles; its average depth is one mile. Within this Delaware-size area of eroded rock rise mountains higher than any in the eastern United States and that dark walls of gorges millions of years old. Agent of this scene, the Colorado River drops 2,200 feet over nearly 200 rapids as it roars through the Canyon toward the Gulf of California.

Numbers, though, tell only part of the canyon's story and merely hint at the magic of its myriad hues, strata, spires, and gorges. The place is more than the sum of its parts-so much more that neither the eye nor the mind of the beholder can encompass more than a small part of it at one time. As John Wesley Powell, whose party in 1869 became the first to traverse the canyon by river, wrote, "You cannot see the Grand Canyon in one view, as if it were a changeless spectacle from which a curtain might be lifted. "

At the canyon's bottom, a mile below the rim, the Colorado River slices through Granite Gorge, exposing some of the oldest rocks visible anywhere on the earth. Nearly two billion years old, the Vishnu schist is the gleaming black remnant of a once towering mountain range. Some 500 million years after it formed, vast rifting and faulting laid it down the tilted, colorful sediments of the Grand Canyon Series atop schist. Ten distinct layers of sandstone, limestone, and shale bespeak the advance and retreat of ancient seas, the building up and wearing down of mountains, the meandering of rivers over 600 million years.

At either rim, visitors to date perch atop creamy Kaibab limestone cliffs studded with fossilized sponges, corals, snails, and shellfish that inhabited a warm inland sea 240 million years ago. Though rock layers once covered this ancient seabed, all geologic signs of the more recent Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras wore away eons ago.

Compared with the nearly two-billion-year process of deposition, erosion has set a brisk pace. The Grand Canyon itself is less than six million years old, created only since the Colorado River changed course and began flowing through the ancestral Colorado plateau. In just two million years, the river sliced to within 500 feet above its current depth. Wind, rain, snow, heat, and cold have helped the process along. So has the flow of hundreds of tributaries, many of which are dry washes, filled intermittently by snowmelt and summer thunderstorms. Over eons these streams have created " a composite of thousands, of tens of thousands, of gorges," as Powell marveled. "Every one of these...is a world of beauty in itself."

The Grand Canyon is not only a slice of North America's geologic history but also a cross section of ecozones. Between rim and river, travelers find the same variety of ecological regions they would encounter on a trip from Canada to Mexico - from the snowy evergreen woods of the boreal zone to the arid depths of the lower Sonoran, where summer temperatures soar above 100oF and tenacious shrubs like creosote and ocotillo predominate. In all, the Grand Canyon provides rich and diverse habitat for more than 400 vertebrate species and 1,500 plants.

The human presence here stretches back at least 4,000 years, beginning with hunter-gatherers who deposited delicate split-willow animal figures in limestone caves. Before disappearing about A.D. 1150, ancient Pueblo peoples who had lived in and around the canyon for a millenium or more left a rich legacy of pottery, baskets, pictographs, and granaries and other structures in thousands of sites. The Havasupai people in the region today trace their presence back hundreds of years.

During the 20th century, humans have had a far more profound impact on the Grand Canyon than in all of the past. By 1900, the canyon was already a well-known destination, thanks to written accounts by explorers and scientists and to the glowing canvases of Thomas Moran. And after Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919, the number of visitors continued to increase exponentially: About five million people now visit the canyon each year by car, on foot, atop mules, on motorized rafts, and in helicopters. Some of the human impact, such as the view-marring haze drifting in from power plants and urban centers, has been indirect. In 1963, the Glen Canyon Dam ended the Colorado River's free flow at the Grand Canyon's entrance, and that single action has changed the canyon more than any other event in human times.

Victoria Falls

|

There are few appropriate superlatives that have not already been applied to this magnificent natural wonder of the world; in many ways it defies description. So vast are the Falls and their setting that it is difficult to grasp their true grandeur and for this reason, they are perhaps best seen from the air.

The Victoria Falls offer an inescapable closeness to the natural elements. The towering column of spray when the river is high, the thunder of the falling water, the terrifying abyss that separates Zimbabwe from Zambia, the forest - lined, placid, tranquil lagoons upstream in which hippo and deadly crocodiles lurk.

David Livingstone reported the existence of the Falls to the outside world in 1860. The result was immediate and from that point, the number of foreign visitors rose steadily. People walked, rode on horseback or traveled by ox - wagon from the Transvaal along what was then called the Hunters Road (now the border between Botswana and Zimbabwe) and on reaching George Westbeech's store at Pandamatenga left their animals there, safe from the lethal bite of the tsetse fly, and walked the remaining 80 kilometers, due north to the Falls.

With the conflict in South Africa finally resolved and the region politically more stable, tourism is developing rapidly. New activities are constantly emerging and the industry is becoming more and more sophisticated. Rafting the wild rapids below the Falls was the first innovation more than ten years ago.

Now the list of organized, commercial activities has expanded dramatically. Visitors can kayak, canoe, fish, go on guided walking safaris, ride on horseback, lunch on Livingstone's Island and in addition to the well-known "Flight of Angels", for the more adventurous there is micro lighting with stunning views of the Falls.

The Harbor of Rio de Janeiro

|

At the beginning of the 16th century, the Portuguese explorers who sailed down Brazil's coast kept tarck of their discoveries, and the days of the year, by naming the former for the latter. On New Year's Day, 1502, they glided toward a narrow opening in the coastline, guarded by fabulously shaped mountains. Beyond this entrance lay a body of water stretching 20 miles inland. Convinced that they had reached the mouth of a great river, they named the area River of the First of January.

The large waterway was not a river; it was an island-studded bay that the Tamoio people had long before named Guanabara - "arm of the sea." Nearly five centuries later, both the native and European names persist. But now, instead of caravels and dugouts, supertankers and yachts glide across the magnificent balloon-shaped harbor of Guanabara Bay. No longer a tropical wilderness teeming with tapirs and jaguars, the bay's western shores now hold a roaring metropolis called Rio de Janeiro - the River of January.

The great bay that looked like a river was only one of many illusions that Rio held. Europeans called the smaller bay of Botafago, under Sugarloaf, a "lake"; the Tamoio themselves named Guanabara Bay's eastern edge Niteroi, meaning "hidden waters." For early European voyagers, it was as though, when Rio hove into view, the curtain rose on a stage set with such strange, striking shapes and forms that virtually everything looked like something else.

Guarding the entrance to the bay, the naked and lopsided mountain the Portuguese called Pao de Acucar evoked the sugarloaves fashioned on the island of Madeira. They called the highest mountain Corcovado - "the hunchback" - for its humped profile. Today, a statue of Christ the Redeemer crowns the 2,300-foot-high peak.

The bay's vastness has been shrinking. With usable land at a premium, landfill has twice altered Guanabara Bay's contours. In the 1920s and again in the 1960s, small hills that once had been home to Rio's earliest settlers were sluiced through pipes to create bayfill. The new land now anchors an airport, a six-lane highway, parkland and beaches, the city's modern art museum, and other 20th-century landmarks as Rio looks to its great bay for elbow room. Paricutin Volcano

|

On the afternoon of February 20, 1943, Dionisio Pulido, a farmer in the Mexican state of Michoacán, was readying his fields for spring sowing when the ground nearby opened in a fissure about 150 fee long. "I then felt a thunder," he recalled later, "the trees trembled, and is was then I saw how, in the hole, the ground swelled and raised it self 2 or 21/2 meters high, and a kind of smoke or fine dust–gray, like ashes–began to rise, with a hiss or whistle, loud and continuous; and there was a smell of sulphur. I then became greatly frightened and tried to help unyoke one of the ox teams."

Virtually under the farmer's feet, a volcano was being born. Pulido and the handful of other witnesses fled. By the next morning, when he returned, the cone had grown to a height of 30 feet and was "hurling out rocks with great violence." During the day, the come grew another 120 feet. That night, incandescent bombs blew more than 1,000 feet up into the darkness, and a slaglike mass of lava rolled over Pulido's cornfields.

The scientific world was almost as stunned as the hapless farmer himself by the volcano's sudden appearance. Around the world, volcanic eruptions are commonplace, but the birth of an entirely new volcano, marked by the arrival at the earth's surface of a distinct vent from the magma chamber, is genuinely rare. In North America, only two new volcanoes have appeared in historic times. One of them was western Mexico's Jorullo, born in 1759 some 50 miles southeast of Dionisio Pulido's property. The second, born about 183 years later in Pulido's field, was named Paricutín for a nearby village that it eventually destroyed.

Paricutín and Jorullo both rose in an area known for its volcanoes. Called the Mexican Volcanic Belt, the region stretches about 700 miles from east to west across southern Mexico. Geologists say that eruptive activity deposited a layer of volcanic rock some 6,000 feet thick, creating a high and fertile plateau. During summer months, the heights snag moisture-laden breezes from the Pacific Ocean; rich farmland, in turn, has made this belt the most populous region in Mexico.

Though the region already boasted three of the country's four largest cities–Mexico City, Puebla, and Guadalajara–the area around Paricutín, some 200 miles west of the capital, was still a peaceful backwater inhabited by Tarascan Indians in the early 1940s. Its gently rolling landscape, in a zone that had experienced almost no volcanic activity during historic times, was one of Mexico's loveliest. Although hundreds of extinct cinder cones rose around the small valleys, the only eruption in human memory had been that of distant Jorullo.

The Tarascan had no folk legends concerning volcanic eruptions in the area. But when Paricutín came into their lives, they saw events, in retrospect, that foretold the cataclysm. The first event was a sacrilege: the 1941 destruction of a large wooden cross on a hillside. The second one hinted at biblical retribution: a plague of locusts in 1942. When 1943 began, so did the third sign: a series of earthquakes; these were preceded, said one man, by "many noises in the center of the earth."

On February 19, the day before the volcano began to erupt, some 300 earthquakes shook the ground. On February 22, with the new cone rising and fiery skyrockets descending, the first of many geologists who would monitor and map Paricutín's behaviour over the next nine years arrived. From then on, Paricutín was under constant observation: It yielded a trove of information, including unique, fleeting glimpses of ephemeral features.

New volcanic phenomena and processes were sometimes obliterated almost as soon as they were recorded, especially during Paricutín's first year of violent, explosive growth and change. In that year, the cone topped 1,100 feet, four-fifths of its final height; explosions echoed all over the state of Michoacan; ash snowed on faraway Mexico City; and almost all of the vegetation for miles around the crater was destroyed.

During the summer of 1943, probably the volcano's most violent period. Lava rose to about 50 feet below the crater's rim. That fall, a new vent opened explosively at the cone's base, fountaining lava high into the sky. Lava finally destroyed the nearby villages the following year, but most villagers has seen their livelihoods disappear long before that.

Over the next years, lava flows continued with little interruption. But in February of 1952, almost exactly nine years after Paricutín was born, the volcano experienced its last major spasm of activity. By then, villages and farms had been relocated with government assistance. The new Bracero Program drew many of the displaced farmers to California for seasonal agricultural work. The Northern Lights

|

Northern lights, or Aurora borealis brings together two mythological deities - Aurora, the Roman goddess of the dawn, and Boreas, Greek god of the north wind - to describe an event witnessed mostly at night in the high northerly latitudes. An identical phenomenon, the aurora australis, occurs in the high latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, a region that has always been much more sparsely inhabited than the planet's northern reaches. Only a few eyewitness accounts of the aurora australis were available before 20th-century explorers arrived in Antarctica.

By contrast, the flowing ribbons, sky-filling swirls, otherworldly glow, gossamer veils, and brilliant rays of the aurora borealis are a regular presence that has awed and terrified northern peoples for thousands of years. To Finns the aurora was "fox fire" sparked by glistening fur. Some Alaskan Inuit saw the dancing souls of deer, seals, salmon, and beluga; others believed that if they whistled the lights might snatch them away. The Athabascan saw messages from their dead, the "sky dwellers."

For a long time, scientists offered almost as many interpretations of the northern lights as did the traditional peoples who observed them. The 20th century has brought with it studies of the earth's magnetism and the sun's workings. The aurora arises in the roiling turbulence of the sun. More than 100,000 times hotter than boiling water, the sun's interior chops the atoms that form solar gases into a thin stream of electrically charged particles - protons and electrons. Both matter and energy, this stream continuously erupts from the sun and is called the solar wind. Two or three days after bursting from the sun's surface at speeds of up to 500 miles a second, the solar wind reaches the earth, 93 million miles away.

The solar wind has the force to swiftly annihilate life on earth. What stops it from doing so is the shielding power of the planet's magnetic field, reaching out more than 40,000 miles into space. Like the earth, the sun is also a mighty magnet, and the solar wind carries fragments of its magnetic field. As solar particles crash into the planet's magnetic field, the fields repel each other.

Though most of the solar wind harmlessly sideswipes the magnetic shield, small streams of solar particles do manage to become trapped, spiraling down toward the planet's north and south magnetic poles. As they tumble, beams of electrons spread, ripple, and swirl, and yet their movements remain invisible. But when the solar wind hits the upper reaches of the ionosphere and encounters atmospheric gases, it starts churning the thin soup of oxygen and nitrogen there. Marvelous shapes and flowing patterns begin to appear. Electrons bouncing around among atoms of oxygen create a greenish glow much lower. Nitrogen molecules hit by solar wind may shine bright pink, or blue and violet, depending upon their distance from the surface.

The ever changing dance of lights belies the aurora's permanence. Though only parts of it can be seen at any time, and almost never during the day, the aurora borealis forms a 2,000-mile-wide auroral oval above the magnetic north pole day in and day out, year after year.

What can dramatically change the oval are the occasional spikes in solar activity that turn the solar wind into a raging hurricane. Then, for a few days, the auroral oval flows toward the Equator and treats sky-gazers as far south as Mexico to midnight extravanganzas. At the same time, electromagnetic disturbances intensify, with overloaded power lines and scrambled communications serving to remind us of the force behind the celestial fireworks.

No comments:

Post a Comment